- Introduction

- Landscape of augmented instruments

- Design choices for the instrument

- Engineering a magnetic scanner

- Controlling the instrument

- Discussion : Compairing with other setups

- Conclusion and future work

- About this website

Introduction

A long tradition of augmented musical instruments

It is easy to forget how refined today's musical instruments are : it took thousands of small experimental changes in design over millenia to lead to the modern masterpieces that are the grand piano or the saxophone. The diversity of acoustic instruments is phenomenal, using vastly different materials and excitation techniques to achieve different timbres or melody styles. Blowing, bowing, picking, stricking, hitting, rubbing, are only a few of the players' possible actions when it comes to producing sound.

But since the beginning, some of these instruments were designed to augment the players capabilities by adding external energy to the production of sound :

Him too whose light touch can elicit loud music from those pipes of bronze that sound a thousand diverse notes beneath his wandering fingers and who by means of a lever stirs to sound the labouring water.

Claudius Claudianus, c. 400 AD 1

This is a description of a water organ which is considered to be the first instrument to use non-human power to produce sound. Many such instruments followed, the most famous of which are the church organ, and its modern companion the Hammond organ. Other electrically amplified instruments, such as the electric guitar, also fit this category. Here the player can produce impressively loud sounds and shape the timbre in a way that is simply impossible using just muscle power.

But augmenting acousting instruments also rapidly took another path, with mechanised automated instruments. These are the barrel organs and serinettes that we tend to associate with popular street music of the 18th century. Music was pre-composed on a roll and played directly, without the need for human intervention. Many mechanised acoustic instruments exist today, and the advent of robotics made them a subject of choice for several mechatronics courses (including two at Mines ParisTech !).

The advent of electricity and new devices like electromagnets opened the way for another modification of acoustic instruments : adding actuators to the original instruments, without removing their manual excitation mechanism, to add new words and articulations to the players's musical vocabulary.

As early as 1886 (hence before the electronic tube), Eisenmann2 used electromagnets to add a sustainer system to a grand piano. His remarkable though fragile design revolved around a mechanical switch connected to the string, which would close periodically to energize the magnet and hence induce a motion in the string. This device aimed at adding usually impossible sounds like infinite notes to the piano sonic possibilities. Many sustainers for stringed instruments were later introduced, mostly using electromagnets to excitate the strings, especially in electric guitars.

A popular product introduced in the 1970s was the E-Bow3, short for electronic bow. An E-Bow is composed of a magnetic pickup and an output electromagnet, connected via an amplifier circuit, creating a positive feedback loop (called Larsen effect) at the resonant frequency of the string. The goal was to allow electric guitarists to play soft, sine-like sustained tones without touching the strings and without modifying their guitar. Several instruments have used this technique of positive feedback or directly fed synthesised signals into actuators to excitate the vibration. These include large systems like the Electromagnetically Prepared Piano4, the Magnetic Resonator Piano5 or the EMvibe6, which add electromagnets to grand pianos and xylophones. They are paired with complex input systems that supplement the usual interfaces of the piano or xylophone, either using an external keyboard (for the EMPP and EM-Vibe) or a sensor bar on top of the piano keys (for the MRP).

Going further in complexity, to modify the shape of the timbre in a more subtle way, researchers began using newly available microcontrollers in the 1990s to shape the vibration of instruments in real-time. They used control theory to model their acoustic properties and added fast actuators to artificially modify the sound characteristics. These new systems, called active control instruments would alter resonant frequencies location or damping coefficients, or even increase the stability of difficult notes. This type of instruments has recently been developed extensively at Ircam by a team lead by Adrien Mamou-Mani, leading to the SmartInstruments family.7

The following diagram sums up the (oversimplified) categories explained above.

A summary of the different types of instruments that add electro-mechanical actuation to the acoustic instrument

Thus, augmented musical instruments have a long history of exploration and extensive research is still lead on their development.

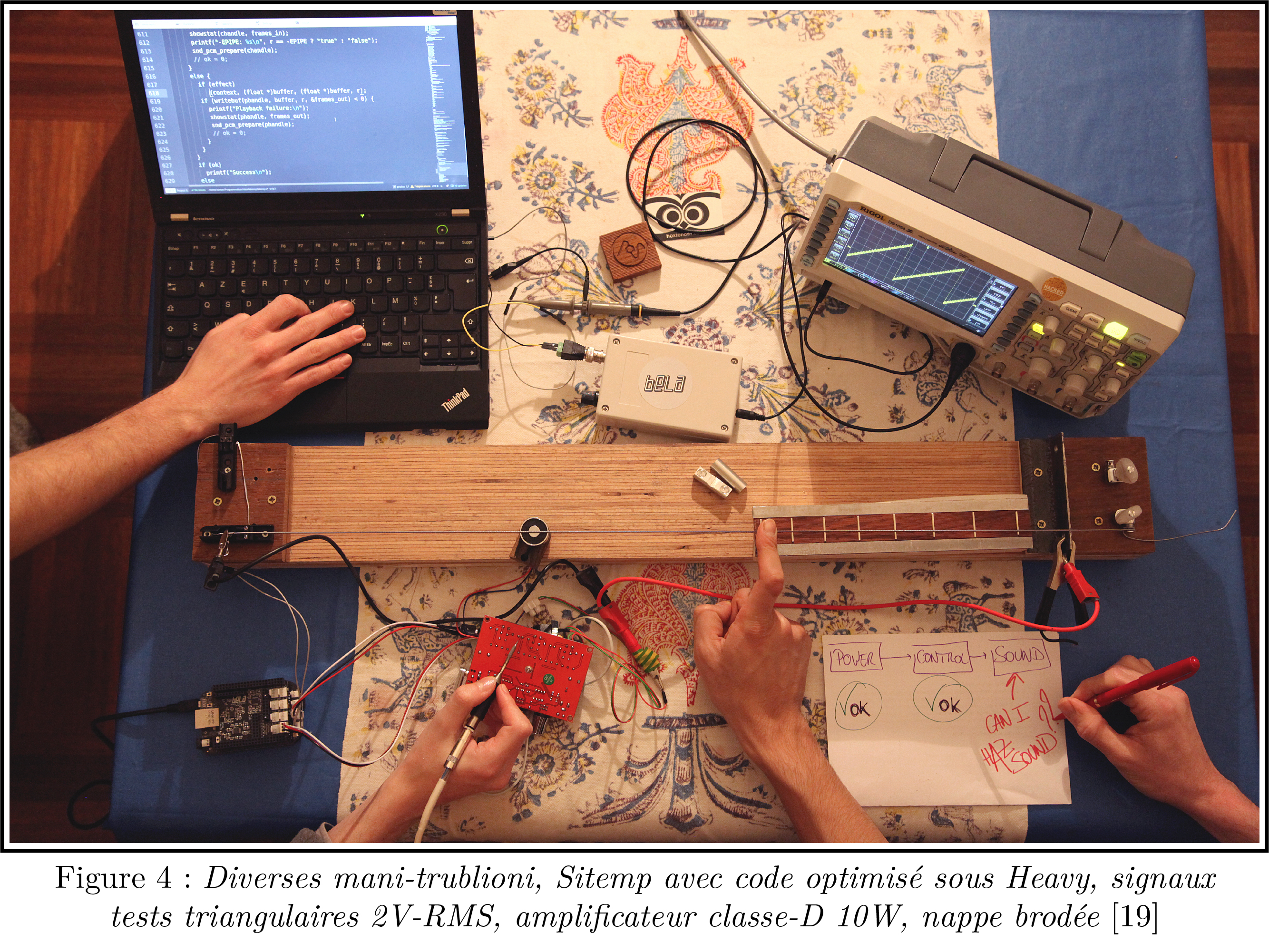

We wanted to try another approach that seemed complementary to the ones introduced above. During our exploration of new augmented instruments, we joined a small association called Trublion that gathers researchers, engineers, makers and musicians around the topic of the creation of new instrumental practices merging physical mechanisms and technological augmentations.

At Trublion

In 2012, electronic music player Florent Colautti built his E-String, a stringed instrument similar to a Chinese Guzheng that uses commercial E-Bows to put the strings into vibration. A microcontroller is used to trigger quickly the actuators according to rythmic patterns, dictated by an external controller. The instrument is also played manually, using small bridges to change the height of the notes.

Trublion initially worked with Florent Colautti to improve his setup : controlling the ebows with a tiny microcontroller, adding embedded preamplifiers, offering the musican a wireless control over the instrument.

However, we wanted to offer the musicians more control over the modification of the timbre, and the possibilities of modifying the exact signals sent to the output electromagnet motivated us to create a separate instrument with a real feedback configuration.

Another proposal

We wanted to build a stringed instrument that was designed with augmentation in mind from the start, rather than building an acoustic instrument and adding control afterwards. Therefore, we did not try to preserve an existing acoustic identity. The instrument is also focused on varying the timbre, and not really on playing melodies. Moreover, having a short history of using electromagnets, we made the opinionated choice of using electromagnets for the actuators. Rather than modifying the acoustic properties in real time or using open loop systems, we wanted to try a combinaison of those techniques to physically reproduce exisiting and new timbres.

In technical terms, we guide the string to make it have the characteristic modal amplitude decays of other instruments. This instrument aims at being hybrid : the musician plays with his hand on the strings and with the computer control system, via an input controller such as a piano keyboard or a more elaborate motion detector.

Methodology

- We started by selecting the sensors and shape of the instrument, and then we put together a test version.

- We then studied the actuators, theoretically and experimentally, by building a magnetic scanner to visualise the actual shape of the magnetic field.

- We later completed the system with a low latency microcontroller and a modal decomposition algorithm.

- We could then test the entire system in open loop and compare it to the results of simple models.

- Finally, we used a proportional controller to make the instrument maintain a specific position in the Fourier space.

- Additionally, as a proof of concept, we applied the results of the magnetic scanner to linearise the effect of the electromagnet to the motion of the string.

Special thanks

We wish to thank the whole team at CAS (Centre for Automation, Mines Paristech), especially Nicolas Petit and Florent Di Meglio for their precious guidance during this internship.

This work would not have been possible without the help and work of Andrew McPherson and his team at the Centre for Digital Music, as the instrument we made owes a lot to the Magnetic Resonator Piano and is entirely built around the Bela system.

Of course we also need to thank the rest of the team at Trublion : Flax for his patience and expertise in the making of the current drive amplifier, Emilien for his help in giving direction to the project and this report, and Fergus for his linux debugging advice.

This project would have been far more difficult without the help of musical instrument maker Léo Maurel, whose advice on building the test instrument was very helpful.

We also want to thank Brigitte d'Andrea (of the CAOR team) for her suggestions on model-free control, which is a promising alternative to the present limited PID controller.

- Benacchio, S., Chomette, B., Mamou-Mani, A. & Finel, V. (2015). Mode tuning of a simplified string instrument using time-dimensionless state-derivative control. Journal of Sound and Vibration. 334: 178–189.

- Berdahl, E., Backer, S. & Smith III, J. . (2005). If I had a hammer: Design and theory of an electromagnetically-prepared piano. Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference. 2005: 81–84.

- Britt, C., Snyder, J. & McPherson, A. (2012). The EMvibe : An Electromagnetically Actuated Vibraphone. Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression. 31–34.

- Claudianus, C. (2016). Claudian with an English Translation by Maurice Platnauer (Complete). Library of Alexandria.

- Heet, G. (1978). Hand held musical string vibration initiator and sustainer.

- McPherson, A. (2010). The Magnetic Resonator Piano: Electronic Augmentation of an Acoustic Grand Piano. Journal of New Music Research. 39(3): 189–202.

- van Eck, C. (2017). Between Air and Electricity: Microphones and Loudspeakers as Musical Instruments. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Introduction

- Landscape of augmented instruments

- Design choices for the instrument

- Engineering a magnetic scanner

- Controlling the instrument

- Discussion : Compairing with other setups

- Conclusion and future work

- About this website